Turing test (nonfiction): Difference between revisions

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

<gallery mode="traditional"> | <gallery mode="traditional"> | ||

File:Cherenkov-radiation Advanced-Test-Reactor.jpg|link=High-energy literature|[[High-energy literature|Cherenkov radiation helps students pass Turing test]], say high energy literature researchers. | File:Cherenkov-radiation Advanced-Test-Reactor.jpg|link=High-energy literature|[[High-energy literature|Cherenkov radiation helps students pass Turing test]], say high energy literature researchers. | ||

File:Electric_Kool-Aid_Acid_Test_cover.jpg|link=The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test|Early techno-thriller fails Turing test, author invents [[High-energy literature]] techniques to improve readability. | |||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

Latest revision as of 09:22, 21 June 2016

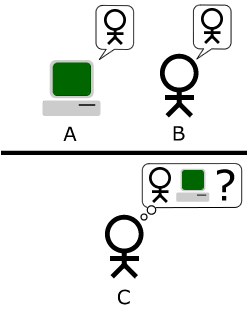

The Turing test is a test, developed by Alan Turing in 1950, of a machine's ability to exhibit intelligent behavior equivalent to, or indistinguishable from, that of a human.

Turing proposed that a human evaluator would judge natural language conversations between a human and a machine that is designed to generate human-like responses.

The evaluator would be aware that one of the two partners in conversation is a machine, and all participants would be separated from one another.

The conversation would be limited to a text-only channel such as a computer keyboard and screen so that the result would not be dependent on the machine's ability to render words as speech.

If the evaluator cannot reliably tell the machine from the human (Turing originally suggested that the machine would convince a human 70% of the time after five minutes of conversation), the machine is said to have passed the test.

The test does not check the ability to give correct answers to questions, only how closely answers resemble those a human would give.

The test was introduced by Turing in his paper, "Computing Machinery and Intelligence", while working at the University of Manchester (Turing, 1950; p. 460).

It opens with the words: "I propose to consider the question, 'Can machines think?'" Because "thinking" is difficult to define, Turing chooses to "replace the question by another, which is closely related to it and is expressed in relatively unambiguous words."

Turing's new question is: "Are there imaginable digital computers which would do well in the imitation game?"

This question, Turing believed, is one that can actually be answered. In the remainder of the paper, he argued against all the major objections to the proposition that "machines can think".

Since Turing first introduced his test, it has proven to be both highly influential and widely criticised, and it has become an important concept in the philosophy of artificial intelligence.

In the News

Cherenkov radiation helps students pass Turing test, say high energy literature researchers.

Early techno-thriller fails Turing test, author invents High-energy literature techniques to improve readability.

Fiction cross-reference

Nonfiction cross-reference

External links:

- Turing test @ Wikipedia

- Alan Turing