Supercritical drying (nonfiction): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

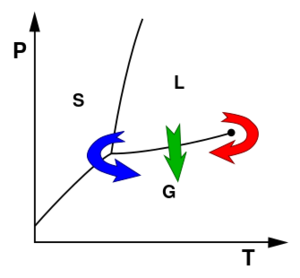

[[File:Supercritical_drying_diagram.svg|thumb|Supercritical drying (red arrow) goes beyond the critical point of the working fluid in order to avoid the direct liquid–gas transition seen in ordinary drying (green arrow) or the two phase changes in freeze-drying (blue arrow).]]'''Supercritical drying''', also known as '''critical point drying''', is a process to remove liquid in a precise and controlled way. It is useful in the production of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), the drying of spices, the production of [[Aerogel (nonfiction)|aerogel]], the decaffeination of [[Coffee (nonfiction)|coffee]] and in the preparation of biological specimens for scanning electron microscopy. | [[File:Supercritical_drying_diagram.svg|thumb|Supercritical drying (red arrow) goes beyond the [[Critical point (thermodynamics) (nonfiction)|critical point]] of the working fluid in order to avoid the direct liquid–gas transition seen in ordinary drying (green arrow) or the two phase changes in freeze-drying (blue arrow).]]'''Supercritical drying''', also known as '''critical point drying''', is a process to remove liquid in a precise and controlled way. It is useful in the production of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), the drying of spices, the production of [[Aerogel (nonfiction)|aerogel]], the decaffeination of [[Coffee (nonfiction)|coffee]] and in the preparation of biological specimens for [[Scanning electron microscope (nonfiction)|scanning electron microscopy]]. | ||

== Phase diagram == | == Phase diagram == | ||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

As the substance in a liquid body crosses the boundary from liquid to gas (see green arrow in phase diagram), the liquid changes into gas at a finite rate, while the amount of liquid decreases. When this happens within a heterogeneous environment, surface tension in the liquid body pulls against any solid structures the liquid might be in contact with. Delicate structures such as cell walls, the dendrites in silica gel, and the tiny machinery of microelectromechanical devices, tend to be broken apart by this surface tension as the liquid–gas–solid junction moves by. | As the substance in a liquid body crosses the boundary from liquid to gas (see green arrow in phase diagram), the liquid changes into gas at a finite rate, while the amount of liquid decreases. When this happens within a heterogeneous environment, surface tension in the liquid body pulls against any solid structures the liquid might be in contact with. Delicate structures such as cell walls, the dendrites in silica gel, and the tiny machinery of microelectromechanical devices, tend to be broken apart by this surface tension as the liquid–gas–solid junction moves by. | ||

To avoid this, the sample can be brought via two possible alternate paths from the liquid phase to the gas phase without crossing the liquid–gas boundary on the phase diagram. In freeze-drying, this means going around to the left (low temperature, low pressure; blue arrow). However, some structures are disrupted even by the solid–gas boundary. Supercritical drying, on the other hand, goes around the line to the right, on the high-temperature, high-pressure side (red arrow). This route from liquid to gas does not cross any phase boundary, instead passing through the supercritical region, where the distinction between gas and liquid ceases to apply. Densities of the liquid phase and vapor phase become equal at critical point of drying. | To avoid this, the sample can be brought via two possible alternate paths from the liquid phase to the gas phase without crossing the liquid–gas boundary on the phase diagram. In freeze-drying, this means going around to the left (low temperature, low pressure; blue arrow). However, some structures are disrupted even by the solid–gas boundary. Supercritical drying, on the other hand, goes around the line to the right, on the high-temperature, high-pressure side (red arrow). This route from liquid to gas does not cross any phase boundary, instead passing through the supercritical region, where the distinction between gas and liquid ceases to apply. Densities of the liquid phase and vapor phase become equal at [[Critical point (thermodynamics) (nonfiction)|critical point]] of drying. | ||

== Fluids == | == Fluids == | ||

Fluids suitable for supercritical drying include [[Carbon dioxide (nonfiction)|carbon dioxide]] (critical point 304.25 K at 7.39 MPa or 31.1 °C at 1072 psi) and freon (≈300 K at 3.5–4 MPa or 25–0 °C at 500–600 psi). [[Nitrous oxide (nonfiction)|Nitrous oxide]] has similar physical behavior to carbon dioxide, but is a powerful | Fluids suitable for supercritical drying include [[Carbon dioxide (nonfiction)|carbon dioxide]] (critical point 304.25 K at 7.39 MPa or 31.1 °C at 1072 psi) and freon (≈300 K at 3.5–4 MPa or 25–0 °C at 500–600 psi). [[Nitrous oxide (nonfiction)|Nitrous oxide]] has similar physical behavior to carbon dioxide, but is a powerful [[Oxidizing agent (nonfiction)|oxidizing agent]] in its supercritical state. Supercritical water is inconvenient due to possible heat damage to a sample at its critical point temperature (647 K, 374 °C) and corrosiveness of water at such high temperatures and pressures (22.064 MPa, 3,212 psi). | ||

In most such processes, acetone is first used to wash away all water, exploiting the complete miscibility of these two fluids. The acetone is then washed away with high pressure liquid carbon dioxide, the industry standard now that freon is unavailable. The liquid carbon dioxide is then heated until its temperature goes beyond the critical point, at which time the pressure can be gradually released, allowing the gas to escape and leaving a dried product. | In most such processes, [[Acetone (nonfiction)|acetone]] is first used to wash away all [[Water (nonfiction)|water]], exploiting the complete [[Miscibility (nonfiction)|miscibility]] of these two fluids. The acetone is then washed away with high pressure liquid carbon dioxide, the industry standard now that freon is unavailable. The liquid carbon dioxide is then heated until its temperature goes beyond the critical point, at which time the pressure can be gradually released, allowing the gas to escape and leaving a dried product. | ||

== See also == | == See also == | ||

* [[Acetone (nonfiction)]] - | |||

* [[Carbon dioxide (nonfiction)]] - | * [[Carbon dioxide (nonfiction)]] - | ||

* [[Coffee (nonfiction)]] | * [[Coffee (nonfiction)]] - | ||

* [[Critical point (thermodynamics) (nonfiction)|Critical point]] - the end point of a phase [[Thermodynamic equilibrium (nonfiction)|equilibrium]] curve. The most prominent example is the liquid-vapor critical point, the end point of the pressure-temperature curve that designates conditions under which a liquid and its vapor can coexist. At higher temperatures, the gas cannot be liquefied by pressure alone. At the critical point, defined by a critical temperature Tc and a critical pressure pc, phase boundaries vanish. Other examples include the liquid–liquid critical points in mixtures. | |||

* [[Miscibility (nonfiction)]] - | |||

* [[Nitrous oxide (nonfiction)]] - | * [[Nitrous oxide (nonfiction)]] - | ||

* [[Oxidizing agent (nonfiction)]] - a substance that has the ability to oxidize other substances — in other words to accept their electrons. Common oxidizing agents are oxygen, hydrogen peroxide and the halogens. | |||

In one sense, an oxidizing agent is a chemical species that undergoes a chemical reaction in which it gains one or more [[Electron (nonfiction)|electrons]]. In that sense, it is one component in an oxidation–reduction (redox) reaction. In the second sense, an oxidizing agent is a chemical species that transfers electronegative atoms, usually [[Oxygen (nonfi ction)|oxygen]], to a substrate. Combustion, many explosives, and organic redox reactions involve atom-transfer reactions. Synonyms: oxidant, oxidizer. | |||

* [[Scanning electron microscope (nonfiction)]] | |||

* [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supercritical_drying Supercritical drying] @ Wikipedia | * [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Supercritical_drying Supercritical drying] @ Wikipedia | ||

[[Category:Nonfiction (nonfiction)]] | [[Category:Nonfiction (nonfiction)]] | ||

Revision as of 05:36, 30 October 2019

Supercritical drying, also known as critical point drying, is a process to remove liquid in a precise and controlled way. It is useful in the production of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), the drying of spices, the production of aerogel, the decaffeination of coffee and in the preparation of biological specimens for scanning electron microscopy.

Phase diagram

As the substance in a liquid body crosses the boundary from liquid to gas (see green arrow in phase diagram), the liquid changes into gas at a finite rate, while the amount of liquid decreases. When this happens within a heterogeneous environment, surface tension in the liquid body pulls against any solid structures the liquid might be in contact with. Delicate structures such as cell walls, the dendrites in silica gel, and the tiny machinery of microelectromechanical devices, tend to be broken apart by this surface tension as the liquid–gas–solid junction moves by.

To avoid this, the sample can be brought via two possible alternate paths from the liquid phase to the gas phase without crossing the liquid–gas boundary on the phase diagram. In freeze-drying, this means going around to the left (low temperature, low pressure; blue arrow). However, some structures are disrupted even by the solid–gas boundary. Supercritical drying, on the other hand, goes around the line to the right, on the high-temperature, high-pressure side (red arrow). This route from liquid to gas does not cross any phase boundary, instead passing through the supercritical region, where the distinction between gas and liquid ceases to apply. Densities of the liquid phase and vapor phase become equal at critical point of drying.

Fluids

Fluids suitable for supercritical drying include carbon dioxide (critical point 304.25 K at 7.39 MPa or 31.1 °C at 1072 psi) and freon (≈300 K at 3.5–4 MPa or 25–0 °C at 500–600 psi). Nitrous oxide has similar physical behavior to carbon dioxide, but is a powerful oxidizing agent in its supercritical state. Supercritical water is inconvenient due to possible heat damage to a sample at its critical point temperature (647 K, 374 °C) and corrosiveness of water at such high temperatures and pressures (22.064 MPa, 3,212 psi).

In most such processes, acetone is first used to wash away all water, exploiting the complete miscibility of these two fluids. The acetone is then washed away with high pressure liquid carbon dioxide, the industry standard now that freon is unavailable. The liquid carbon dioxide is then heated until its temperature goes beyond the critical point, at which time the pressure can be gradually released, allowing the gas to escape and leaving a dried product.

See also

- Acetone (nonfiction) -

- Carbon dioxide (nonfiction) -

- Coffee (nonfiction) -

- Critical point - the end point of a phase equilibrium curve. The most prominent example is the liquid-vapor critical point, the end point of the pressure-temperature curve that designates conditions under which a liquid and its vapor can coexist. At higher temperatures, the gas cannot be liquefied by pressure alone. At the critical point, defined by a critical temperature Tc and a critical pressure pc, phase boundaries vanish. Other examples include the liquid–liquid critical points in mixtures.

- Miscibility (nonfiction) -

- Nitrous oxide (nonfiction) -

- Oxidizing agent (nonfiction) - a substance that has the ability to oxidize other substances — in other words to accept their electrons. Common oxidizing agents are oxygen, hydrogen peroxide and the halogens.

In one sense, an oxidizing agent is a chemical species that undergoes a chemical reaction in which it gains one or more electrons. In that sense, it is one component in an oxidation–reduction (redox) reaction. In the second sense, an oxidizing agent is a chemical species that transfers electronegative atoms, usually oxygen, to a substrate. Combustion, many explosives, and organic redox reactions involve atom-transfer reactions. Synonyms: oxidant, oxidizer.

- Supercritical drying @ Wikipedia